Apollonian circles

-

- This article discusses a family of circles sharing a radical axis, and the corresponding family of orthogonal circles. For other circles associated with Apollonius of Perga, please see the disambiguation page, circles of Apollonius.

Apollonian circles are two families of circles such that every circle in the first family intersects every circle in the second family orthogonally, and vice versa. These circles form the basis for bipolar coordinates. They were discovered by Apollonius of Perga, a renowned Greek geometer.

Contents |

Definition

The Apollonian circles are defined in two different ways by a line segment denoted CD.

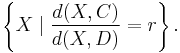

Each circle in the first family (the blue circles in the figure) is associated with a positive real number r, and is defined as the locus of points X such that the ratio of distances from X to C and to D equals r,

For values of r close to zero, the corresponding circle is close to C, while for values of r close to ∞, the corresponding circle is close to D; for the intermediate value r = 1, the circle degenerates to a line, the perpendicular bisector of CD. The equation defining these circles as a locus can be generalized to define the Fermat–Apollonius circles of larger sets of weighted points.

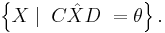

Each circle in the second family (the red circles in the figure) is associated with an angle θ, and is defined as the locus of points X such that the inscribed angle CXD equals θ,

Scanning θ from 0 to π generates the set of all circles passing through the two points C and D.

Pencils of circles

Both of the families of Apollonian circles are called pencils of circles. More generally, there is a natural correspondence between circles in the plane and points in three-dimensional projective space; a line in this space corresponds to a one-dimensional continuous family of circles called a pencil.

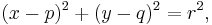

Specifically, the equation of a circle of radius r centered at a point (p,q),

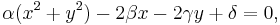

may be rewritten as

where α = 1, β = p, γ = q, and δ = p2 + q2 − r2. However, in this form, multiplying the 4-tuple (α,β,γ,δ) by a scalar produces a different four-tuple that represents the same circle; thus, these 4-tuples may be considered to be homogeneous coordinates for the space of circles.[1] Straight lines may also be represented with an equation of this type in which α = 0 and should be thought of as being a degenerate form of a circle. When α ≠ 0, we may solve for p = β/α, q = γ/α, and r =√((−δ − β2 − γ2)/α2); note, however, that the latter formula may give r = 0 (in which case the circle degenerates to a point) or r equal to an imaginary number (in which case the 4-tuple (α,β,γ,δ) is said to represent an imaginary circle).

The set of affine combinations of two circles (α1,β1,γ1,δ1), (α2,β2,γ2,δ2), that is, the set of circles represented by the four-tuple

for some value of the parameter z, forms a pencil; the two circles are called generators of the pencil. There are three types of pencil:[2]

- An elliptic pencil (red family of circles in the figure) is defined by two generators that pass through each other in exactly two points (C and D). At these points, the defining formula has zero value, and therefore will also equal zero for any affine combination. Thus, every circle of an elliptic pencil passes through the same two points. An elliptic pencil does not include any imaginary circles.

- A hyperbolic pencil (blue family of circles in the figure) is defined by two generators that do not intersect each other at any point. It includes real circles, imaginary circles, and two degenerate point circles (here C and D) called the Poncelet points of the pencil. Each point in the plane belongs to exactly one circle of the pencil. forms a pencil of this type.

- Finally, a parabolic pencil (as a limiting case) is defined where two generating circles are tangent to each other at a single point . It consists of a family of real circles, all tangent to each other at a single common point. The degenerate circle with radius zero at that point also belongs to the pencil.

A family of concentric circles centered at a single focus C forms a special case of a hyperbolic pencil, in which the other focus is the point at infinity of the complex projective line. The corresponding elliptic pencil consists of the family of straight lines through C; these should be interpreted as circles that all pass through the point at infinity.

Radical axis and central line

Except for the two special cases of a pencil of concentric circles and a pencil of coincident lines, any two circles within a pencil have the same radical axis, and all circles in the pencil have collinear centers. Any three or more circles from the same family are called coaxal circles or coaxial circles.[3]

The elliptic pencil of circles passing through the two points C and D (the set of red circles, in the figure) has the line CD as its radical axis. The centers of the circles in this pencil lie on the perpendicular bisector of CD. The hyperbolic pencil defined by points C and D (the blue circles) has its radical axis on the perpendicular bisector of line CD, and all its circle centers on line CD.

The radical axis of any pencil of circles, interpreted as an infinite-radius circle, belongs to the pencil. Any three circles belong to a common pencil whenever all three pairs share the same radical axis and their centers are collinear.

Inversive geometry, orthogonal intersection, and coordinate systems

Circle inversion transforms the plane in a way that maps circles into circles, and pencils of circles into pencils of circles. The type of the pencil is preserved: the inversion of an elliptic pencil is another elliptic pencil, the inversion of a hyperbolic pencil is another hyperbolic pencil, and the inversion of a parabolic pencil is another parabolic pencil.

It is relatively easy to show using inversion that, in the Apollonian circles, every blue circle intersects every red circle orthogonally, i.e., at a right angle. Inversion of the blue Apollonian circles with respect to a circle centered on point C results in a pencil of concentric circles centered at the image of point D. The same inversion transforms the red circles into a set of straight lines that all contain the image of D. Thus, this inversion transforms the bipolar coordinate system defined by the Apollonian circles into a polar coordinate system. Obviously, the transformed pencils meet at right angles. Since inversion is a conformal transformation, it preserves the angles between the curves it transforms, so the original Apollonian circles also meet at right angles.

Alternatively,[4] the orthogonal property of the two pencils follows from the defining property of the radical axis, that from any point X on the radical axis of a pencil P the lengths of the tangents from X to each circle in P are all equal. It follows from this that the circle centered at X with length equal to these tangents crosses all circles of P perpendicularly. The same construction can be applied for each X on the radical axis of P, forming another pencil of circles perpendicular to P.

More generally, for every pencil of circles there exists a unique pencil consisting of the circles that are perpendicular to the first pencil. If one pencil is elliptic, its perpendicular pencil is hyperbolic, and vice versa; in this case the two pencils form a set of Apollonian circles. The pencil of circles perpendicular to a parabolic pencil is also parabolic; it consists of the circles that have the same common tangent point but with a perpendicular tangent line at that point.[5]

See also

Notes

- ^ Pfeifer & Van Hook (1993).

- ^ Schwerdtfeger (1979, pp. 8–10).

- ^ MathWorld uses “coaxal,” while Akopyan & Zaslavsky (2007) prefer “coaxial.”

- ^ Akopyan & Zaslavsky (2007), p. 59.

- ^ Schwerdtfeger (1979, pp. 30–31, Theorem A).

References

- Akopyan, A. V.; Zaslavsky, A. A. (2007), Geometry of Conics, Mathematical World, 26, American Mathematical Society, pp. 57–62, ISBN 978-0-8218-4323-9.

- Pfeifer, Richard E.; Van Hook, Cathleen (1993), "Circles, Vectors, and Linear Algebra", Mathematics Magazine 66 (2): 75–86, doi:10.2307/2691113, JSTOR 2691113.

- Schwerdtfeger, Hans (1979), Geometry of Complex Numbers: Circle Geometry, Moebius Transformation, Non-Euclidean Geometry, Dover, pp. 8–10.

- Samuel, Pierre (1988), Projective Geometry, Springer, pp. 40–43.

- Ogilvy, C. Stanley (1990), Excursions in Geometry, Dover, ISBN 0-486-26530-7.

External links

- Weisstein, Eric W., "Coaxal Circles" from MathWorld.